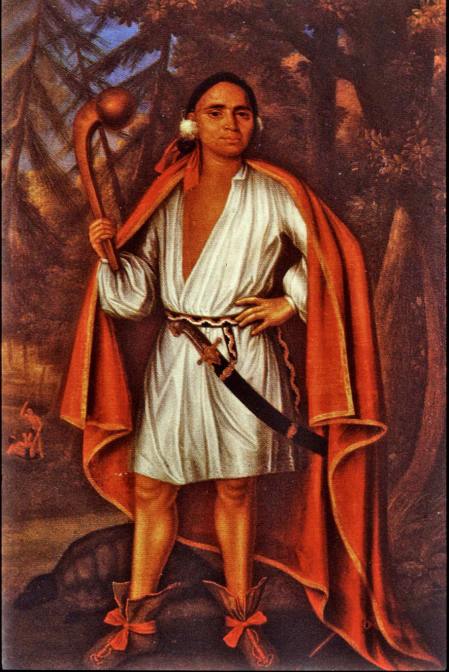

On the walls of the National Portrait Gallery of Canada hangs a 305 year old portrait of “Et Oh Koam”, one of the “Four Mohawk Kings” by Dutch painter John Verelst on display there.

On the walls of the National Portrait Gallery of Canada hangs a 305 year old portrait of “Et Oh Koam”, one of the “Four Mohawk Kings” by Dutch painter John Verelst on display there.

Neither a Mohawk nor a king exactly, Etowaukaum was in fact an important sachem of the Muhheconnuck, or Mohican people, later consolidated and referred to as the “Stockbridge Indians.” While little is recalled of his life, this former Berkshire resident had not only a key role in the history of his own people, but along with his three Mohawk companions had profound impacts on the literature, theatre, and social philosophy of England in the early 18th century

Though unlike most of his Mohican contemporaries his likeness has been preserved for posterity, only scant biographical details of Etowaukaum survive in historical record. He is generally believed to have served as the chief sachem of the Mohicans in the early 18th century, between the death of Wattawit sometime in the 1690s and the ascendance of Ampamit as chief sachem by the 1730s.

His greatest fame came in 1710, when he along with several Mohawk sachems of the Iroquois traveled to London as the guests of Queen Anne. Though only a little over two weeks in length, the trip was to have a demonstrable lasting impact on the British psyche.

Native Americans had been seen in the country before over the past fifty years, but under different circumstances. Most were abducted by force, like Squanto, by explorers and early colonists who saw the indigenous Americans as a rare and valuable slave commodity. Certainly, none had ever been feted as the guests of European royalty, and unprecedented excitement in London greeted the four visiting “Kings of America.”

The trip was organized by Colonel Peter Schuyler, who had served as Albany’s first mayor and twice became acting governor of the New York province. In part, the sachems were there to request that England send Christian missionaries to their villages, but the diplomatic venture was also in the context of the broader saga of the ongoing contest with the French for dominion over North America.

Schuyler had strong ties among the Mohawk as well as the Mohican tribes, who the year prior had participated in the military campaign he’d commanded against Canada.

“This 1709 expedition against Canada had been abandoned without notice, leaving the colonies embarrassed and their Indian allies frustrated and annoyed,” according to historian Shirley Dunn.

So Schuyler’s Albany group had come, along with representatives of their Iroquois and Algonquin allies, to lobby Queen Anne and her advisers to resume support for resuming the assault. Those chosen to travel to London came from among some of the native leadership Schuyler knew best.

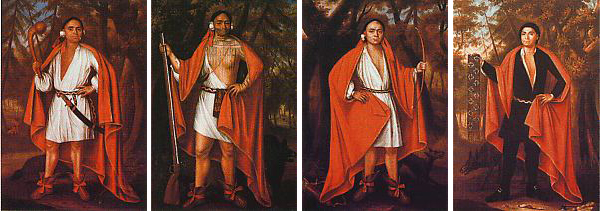

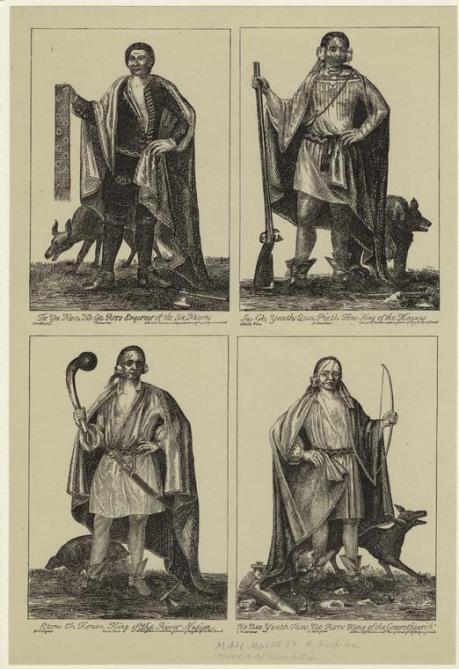

Like his three companions, Etowaukaum had at some point been baptized Christian, and had been given the name Nicholas. His three Mohawk companions were Te Yee Neen Ho Ga Prow, or Hendrick; Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, (Brant), Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row (John).

Hendrick, the youngest, would become a figure on ongoing importance to the English and Iroquois alliance, and eventually die fighting the French at Lake George in 1755. It was he who spoke for them in presenting their position in audience with Queen Anne on April 19, 1710.

Speaking in his own native tongue through translators, Te Yee Neen Ho Go Prow spoke of how in the recent conflict with the French his people had “put away the kettle and taken up the hatchet, and yet expected help from England had not come.”

Gently he reminded the Queen that they had been “a strong wall of security” for the English colonists, “even to the loss of our best men,” and suggested that the reclamation of Canadian territory from the French was vital to Mohawk hunting and trading with the English. He warned, however, that if England did not resume support soon, they might be forced to stand neutral in future conflict.

They then presented wampum belts to the Queen, in the standard tradition of Iroquois diplomacy. In retrospect, the entire audience had the result of introducing England to the format of the Iroquois treaty council, and a concept of autonomy and sovereignty of the natives which would more or less continue to be honored by England and its colonists in negotiation until the late 1700s.

Throughout the rest of their stay, the four continued to be treated as visiting royalty, and presented as the “Four Indian Kings,” or “Four Kings of Canada,” though none of them lived in Canada. Each day they were spirited about in carriages to see sights, be banquets given for them by the nobility, to theaters and most especially to displays of the empire’s military might, from a review of British troops in Hyde Park to tours of some of the Royal Navy’s most powerful ships.

Throughout the rest of their stay, the four continued to be treated as visiting royalty, and presented as the “Four Indian Kings,” or “Four Kings of Canada,” though none of them lived in Canada. Each day they were spirited about in carriages to see sights, be banquets given for them by the nobility, to theaters and most especially to displays of the empire’s military might, from a review of British troops in Hyde Park to tours of some of the Royal Navy’s most powerful ships.At each destination, crowds flocked to see them, the sensation around their visit rising to fever pitch. At a performance of MacBeth at the Haymarket Theater advertised as “For the entertainment of the Four Indian Kings,” crowds became restless and finally stopped the show, clamoring that they had come to see the four kings.

“The kings we will have!” the crowd roared louder and louder, until the lead actor had to stop in the midst of his lines to assure them that the kings were there, enjoying the show from the front box. This only excited the crowd more in its clamors to see them, until at last chairs were brought so the four could sit in full view on the stage throughout the rest of the performance.

Word spread of the turnout at the theatre, and throughout the next few days a barrage of plays, concerts, puppet shows, and even cockfights were advertised as being presented for the enjoyment of the Four Indian Kings, far more events than they could possibly have attended.

Verelst was commissioned for their portraits, whose trappings represent a mix of native concepts and English ones. Etowaukaum, for instance, is shown with a large turtle at his feet, meant to illustrate that he was a member of the turtle clan. His wardrobe is a mix of his own traditional garb with English garments; all four of are draped with red capes and posed in a manner meant to play to a European image of royal appearances. Hendrick is shown almost entirely in black, because it was done while the Court was in mourning over the death of the queen’s consort.

What the visiting Americans thought of all this anyone’s guess, their thoughts on the journey were not recorded -or if they were, were not preserved. What was lacking in first hand impressions, though, London scribes were happy to fill in for in fictionalized accounts.

In 1711, The Spectator, a widely circulated daily paper by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, published a series of writings purported to be drawn from papers left behind by the Mohawk Kings. Despite the fact that they had no written language, the manuscript allegedly acquired by The Spectator proceeds to lay out a series of observations by the chieftains on facets of British society ranging from politics to fashion.

Various poets and playwrights followed suit, and the use of the Four Kings as literary characters and devices for social commentary continued over the next few decades. Even Jonathan Swift once complained, in a letter, that the Spectator had purloined his idea for part of a future novel he was contemplating, suggesting that the then-legendary visit of the Mohawk leaders had some influence on what would eventually become Gulliver’s Travels.

They had become an important part of Europe’s increasing desire to view itself from an external perspective, especially that of the “primitive” or “natural man.” Ongoing tales of their exploits in England persistent throughout the 18th century helped cement a foundation for the growing concept of the Noble Savage, the romanticism of primal innocence in nonindustrial peoples that still holds so much sway in the modern imagination.

While their impact on the popular culture of England may have the most lasting legacy of their visit, it was not without some results for their own people. Though Queen Anne made no promises regarding the support sought by Schuyler and his Albany companions, she did refer the request for missionaries to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who sped it along through the proper committee. By 1711, authorization was given for the construction of a fort, a chapel, and missionary’s house at Fort Hunter, New York to serve the Mohawks there. Missionaries were instructed to begin teaching English to the native children as well as instructing English youth in the Mohawk language.

Missionary outreach for Etowaukaum’s “People of the River” was much slower in coming. It was not until 1734, after a gathering called by Mohican leaders Konkapot and Umpachanee ended with a renewed request, that John Sergeant was sent to live with them at Stockbridge.

It’s unclear whether Sergeant met Etowaukaum, who died in 1736 at the Mohican settlement at Kanaumeek (New Lebanon), but knew members of his family well. Umpachanee married Etowaukaum’s daughter, and later their son, Jonas Etowaukaum, accompanied Sergeant when he left for Yale for several months to be educated in English ways.

Jonas Etowaukaum died fighting the French on behalf of the British at Ticonderoga in 1759, one of hundreds of Mohican slain in battle over several decades of their alliance with the English colonists.

Images: Portraits by John Verelst 1710, engravings based on Velest’s portraits by printmaker John Simon 1750,